BECTU History Project

|

Speaker key: KM=Katie Megan YV=Yvette Vanson

|

BECTU is a trade union which represents workers in production and independent broadcasting, arts and entertainment and is the largest union at the BBC. Yvette was an active member for many years.

|

KM: This is an interview with Yvette Vanson by Katie Megan on the 22nd of June 2007 for the BECTU History Project with whom all copyright remains vested. Yvette, over the past 20 years you’ve been working as a maker of challenging documentary films for television. Your work has been described by critics as 'television of a high order, well crafted, and aimed unerringly to engage both intellect and emotions', and you recently donated the Vanson Wardle and Vanson Productions collections to the BFI, and your work constitutes an invaluable film resource charting some of the major political events throughout the 1980s and early ‘90s. Let’s start this interview by talking about maybe your family background, where you were born.

|

|

YV: I'm a Surrey girl. I was born in Walton-on-Thames. I have an elder sister, Louise, who was at the BBC as a designer, and then has had a very successful prop company at Shepperton Studios for 30 years [Keir Lusby Props]. My father, Paul, worked at Cartier, the jewellers. He’s still alive. He’s 92, and a good socialist all his life. A bit of a contradiction working at Cartier and being a Labour councellor. [He died in 2008]. He is half French, hence my name, Yvette, and my mother, Sarah, was from cockney Jewish stock and she worked for Ralph Marshall Agency, representing variety acts, securing them bookings with Stoll and Moss Empire Theatres and international tours in the entertainment business when she met my father, but then gave it up to be a mum. She died about three years ago. So, sort of a small nuclear family in suburbia.

|

KM: You attended the Kingston Polytechnic, if I'm right?

YV: That’s right. It’s the University of Kingston now.

KM: Right, in the late ‘70s where you gained a first class honour in social science. So, am I right in assuming that a future career in social documentary filmmaking was seeded at quite an early age, because I know you moved into acting quite early on as well?

|

YV: I was an actress. I went to the Welsh College of Music and Drama, which is now the Royal College of Music and Drama, in Cardiff and I did some work in television and then theatre, and I was in the West End with David Warner in I, Claudius and things like that. So I had seven years quite successful career as an actress.

|

|

But then I got frustrated with that and went to Kingston to read social science, and one day I was in a lift and two blokes got in the lift. They started chatting me up basically, and they asked 'what are you doing?’ and I told them, and I said ‘what do you do?’ and they said ‘we run a studio’. There was a little studio at Kingston Poly and nobody had told anybody about it and nobody used it and they were in danger of losing their jobs.

|

Funnily enough, one of them [Ergin Ahmet] went on to be at Channel Four and is very active in BECTU. Anyway, the upshot of that was that I made a programme with them as part of my degree and I was one of the early students to do it.

KM: What was that about?

KM: What was that about?

YV: That was called Objectivity in the News – Fact or Fallacy. And actually, now that I think back on it, it was great. I got to talk to people like Stuart Hood, BBC Controller of Programmes 1961- 64, David Elstein, Brian Winston, I mean, all sorts of people. I did a case study on the Ford workers, we documented the news and looked at it and tried to analyse it. Anyway, it was quite a project really. It was editing by pressing buttons!

But it got me a job at the BBC straight after my university degree. Or rather it didn’t, because in 1979 I got a job at the Community Programme Unit at the BBC with Mike Fentiman, he took me on, and then I was blacklisted.

KM: Right, because you were a member of the Worker’s Revolutionary Party at one point, weren’t you?

But it got me a job at the BBC straight after my university degree. Or rather it didn’t, because in 1979 I got a job at the Community Programme Unit at the BBC with Mike Fentiman, he took me on, and then I was blacklisted.

KM: Right, because you were a member of the Worker’s Revolutionary Party at one point, weren’t you?

YV: I was. I printed off the article about blacklisting in room 105 at the BBC, and I was in very good company. John Goldschmidt was blacklisted, Michael Rosen, Richard Gott - there were loads of people and probably hundreds of people who don’t even know about it. But there was an article written in ’85 by David Leigh and Paul Lashmar, sort of outing what was going on and we all put our name to it thinking this is only going to make things worse, but in fact it was good. I think it was a good thing to do because it was iniquitous.

KM: So you were taken on?

KM: So you were taken on?

YV: So I was taken on and I kept waiting for my contract to arrive, and it didn’t arrive and I rang Mike Fentiman two or three weeks before I was due to start. I said ‘where’s my contract?’ and he said ‘oh, there’s been a bit of a glitch. I've been told to employ somebody internally’. And I went, ‘verbal contract, I want to come. It’s a great unit’. I said ‘I don’t believe this Mike. I think there’s more to this. Go away and investigate’. He did and he went away and he spoke to Stuart Hood [Controller of Programmes] when he was still there. Basicically they admitted to him that it was because of my past political activity. But I hadn’t been in the WRP for years, and it was just ridiculous. Anyway, I didn’t get the job. I got £500 compensation, and it potentially changed the whole of my career, where might I have ended if I'd been at the BBC? It could have been for the worse; it could have been for the better, who knows?

KM: So of course it’s common knowledge now that this secret vetting system by the MI5 had been going on for decades.

KM: So of course it’s common knowledge now that this secret vetting system by the MI5 had been going on for decades.

YV: At the time it was really shocking, and it made a huge difference to my career. I had to start reapplying for jobs. You can imagine, I'd got my first class degree, got a job at the BBC and then I didn’t, and I had nothing but this little film I'd made. But I wanted to do television anyway, and I ended up in Ruskin. I made some tape slide productions for the Ruskin College education arm of the trade union group there. We did videos on the Brandt Report and multinational corporations and then we made some videos about workers rights. I was there for about a year and a half.

KM: So sort of training.

KM: So sort of training.

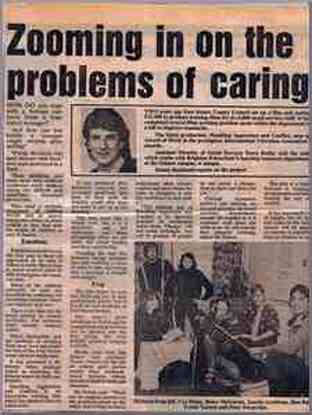

YV: Training and educational campaigning. And then I got the job at East Sussex Social Services, which was completely incredible. For a social services department to allocate funds for staff training using video, and to invest in cameras and people, me, was incredible. There was a very innovative director of social services, and he took me on.

I mean, I had no experience really, but he saw something, and it was a fantastic learning curve because I made 30 films. We had a small unit, we had our own gear they bought, we did training workshops for social services staff, and we developed all these training tools, which were very, very innovative.

I mean, I had no experience really, but he saw something, and it was a fantastic learning curve because I made 30 films. We had a small unit, we had our own gear they bought, we did training workshops for social services staff, and we developed all these training tools, which were very, very innovative.

|

So now people think of John Cleese, but we were doing similar things, like on mental health. We did small video cameos [which were used by trainers as triggers to aid discussion] and I used actors. I thought ‘this is great, I'll do drama’. So I got some very experienced actors, people like Jimmy Marcus who had been in The Clockwork Orange, Vicky Williams, Ishia Bennison, Oliver Ford Davies - I got a little team of people and they came down because they were my friends really. I think that’s when Tony started writing some of the scripts in East Sussex, Tony Wardle, [my partner] and we did lots and lots of this training material. It was used for years. It was sold internationally, but it was very funny at times working with social workers.

|

I used to walk in and I used to kiss people hello, and they’d go ‘oh’, and they’d use this terminology, and I'd put my hand up in the meetings and say ‘excuse me, could you just speak English?’ So I was thought of as a bit of a character. But it worked and I was very proud of the fact we made films for home helps and people like that.

|

YV: That was my naivety as a filmmaker because I thought, how can we get social workers to get inside the mind of a child? So, [I decided], we’ll do the film with the camera as the child. Well, I mean, anyone now would know it’s the hardest thing in the world to do, to do everything from that point of view …where the camera is the point of view of somebody. But in naivety you do these things, and we pulled it off. It really gave a sort of immediacy to it. So everyone Jimmy encountered was either looking straight at camera or ignoring the camera, as [if it were] a child, it was very powerful.

|

KM: There seemed to be a lot of energy and humour, you know, given some of the projects might have been – in a way – quite dry subject matter.

YV: Oh yes, we came at it in a completely different way, because obviously some of it was very heavy. I was still a member of Equity, so I presented a whole package on the Mental Health Act when it came out.

|

We developed these training packs, and that was really quite important because we used video links, written word, we worked with trainers and social workers and so on. So we did one on handling aggression, very important things for social workers who are dealing with very, very difficult teenagers for example, or for senile dementia.

|

Now a lot of these things are currently in documentaries, in the press, in the media, but at the time it was challenging stuff and new. I really enjoyed it and I worked with some good people.

KM: You worked very closely with Tony Wardle for about 16 years?

YV: Yes, 16, 17 years.

KM: You mentioned he was writing some of these, but when did you first work with him?

YV: Yes, 16, 17 years.

KM: You mentioned he was writing some of these, but when did you first work with him?

|

YV: We first got together as friends and lovers, I have to say. So it was an emotional getting together, and without going into too much detail, he was driving lorries at the time on the continent, and I'd just finished at Ruskin. Anyway, the job came up in Sussex and it was a question by then of if he was going to come with me. He had been a journalist, he is a wonderful journalist, and he’d just had a glitch in his life. He’d done a lot of writing, particularly for women’s magazines, some very strong articles.

So it was a really good team, although the emotional relationship didn’t last, the team carried on for a lot longer. He was a very good interviewer, very strong. He’s a very empathetic, nice guy, intelligent and extremely good at research, digging things out.

|

I really worry that we’re losing that research element of work. It’s hard work, but it pays off because you meet really good people. You meet them, you don’t just read about them on a screen. So he would do a lot of the preparatory research and I would hold the business together and pull it together and do the directing.

KM: So you and Tony first started working with East Sussex social services.

|

YV: Yes. I had a parallel career alongside broadcast, and some of it I did on my own initially, and then we started Vanson Wardle later. It was a parallel universe which was us doing a lot of non-broadcast videos for charities mainly, sort of coming out of East Sussex. So we met people from the Spastic Society, it is now called SCOPE, and Leonard Cheshire.

|

For years we did loads and loads of these training films, some PR films for charities, mainly in the sort of social area. Tony was rumbling along doing that when I went off to the BBC. I finally got into the BBC after my blacklisting. Mike Fentiman, the same man, stuck his neck out for me in ’84 and took me on at the Community Programme Unit. I only was ever at the BBC on a contract for six months. I think they extended it by two months, but that was it.

|

The first thing we did at the BBC was Advocacy, which was a four part series which we did in the studio. Peter Lee Wright was one of the directors, and I produced a couple of them. We were looking for a presenter and we interviewed various people to present. We interviewed people like Patricia Scotland, who was a QC, and we interviewed a lawyer called Michael Mansfield and he presented it… and I fell in love with him. We have been together for 23 years (since divorced).

|

We did this series and it was incredible. At one point we had 70 striking health workers, women who were outside [picketing] one of the hospitals. They were cleaners and they [the health authority] were trying to privatise the services. So we had them all in and we had this great debate going on, which Michael mediated, between the employers and the people who were on strike, or whatever, some experts and so on. It was good and we did about four of them. We should have done some more really.

KM: And then you made Taking Liberties.

|

YV: Taking Liberties was very important. We went to Yorkshire during the miner’s strike. I'd lived a bit in my life, and I liked to think I knew what was going on in the world, and I was a political woman, but I was really shocked when I went to Yorkshire and saw the extent of the police state we were living under.

One of the important things about Taking Liberties I think is [the sequence when] we were in a van. We tried to take a couple of miners, they were going picketing, in a van, across the border to Nottingham from Yorkshire, and we were stopped by the police and we captured it on camera. It was just absolutely devastating that we were turned back. There was no freedom of speech and there was no freedom of association. |

We got footage, but we also reconstructed incredibly, the police chasing through people’s houses in Yorkshire, the washing coming off the line, which of course was in Billy Elliot. I had lunch with the director, Stephen Daldry, and he used some of the images of the miner’s strike that we shot in Taking Liberties as ideas for Billy Elliot.

|

The point about Taking Liberties as well was they [the BBC hierarchy] threatened Mike Fentiman and Tony Laryea, who were the editor and the assistant editor, with closure of the whole unit, over that film. They did not like it. It was very political, it was very damaging to the police, and they said you can’t put this out. They [Mike & Tony] fought, but I wasn’t allowed to be there.

|

Often, as a producer, the frustrating thing is that you are not allowed in on the discussion with the commissioning editors or the head of the BBC or wherever it’s going, and you cannot fight to defend your film. So you are totally reliant on your commissioning editors, or the head of your department, in this case Mike Fentiman, to fight your corner. Well, they did fight. They were fantastic.

I remember Tony Laryea coming back nearly in tears saying ‘we’ve lost it, you’re going to have to cut this Yvette, you’re going to have to take this out; you have to change it. We can’t say that’. We said ‘No, we have to fight this’. It’s a lesson. You have to really fight for what you believe in. It was important.....

I remember Tony Laryea coming back nearly in tears saying ‘we’ve lost it, you’re going to have to cut this Yvette, you’re going to have to take this out; you have to change it. We can’t say that’. We said ‘No, we have to fight this’. It’s a lesson. You have to really fight for what you believe in. It was important.....

KM: So then you kind of stuck with the whole issue of the sort of government’s assault on the mining industry.

YV: Somewhere along the line I worked for Channel Four for a company, Skyline, but it was a series called Years Ahead, and I did a few months there. The only reason I mention that is because I worked there freelance after the BBC, I suppose. This guy called Steve Clarke Hall who is now a very well known film producer, a very successful one, we made little inserts for an elderly magazine programme.

It was just like the miners, men on horseback, batons, battering them over the head. It was censored. They wouldn’t put it out. I left the job, and I was great friends with Steve Clarke Hall but they wouldn’t put it out. I don’t actually know what happened.

I was really disappointed about that. Somewhere in the BFI you have a little reel of it. It’s eight minutes long. So that was one of the early censorships that went on. But you are right; I carried on with the whole miner’s issue into Orgreave, because by that time I'd met my husband, Michael Mansfield. He was defending miners who were charged with riot after picketing at Orgreave, which was a coking plant in Yorkshire. There had been terrible scenes there at a mass picket and a lot of contretemps between the police and miners.

I was really disappointed about that. Somewhere in the BFI you have a little reel of it. It’s eight minutes long. So that was one of the early censorships that went on. But you are right; I carried on with the whole miner’s issue into Orgreave, because by that time I'd met my husband, Michael Mansfield. He was defending miners who were charged with riot after picketing at Orgreave, which was a coking plant in Yorkshire. There had been terrible scenes there at a mass picket and a lot of contretemps between the police and miners.

I decided to make a film [The Battle for Orgreave] about the trial that he was conducting. The trial was 48 days long and I did something which again then was very unusual. I mean, somebody will tell you that of course it happened in the ‘30s, but at that point, most documentaries were fairly dry, sitting on sofas like this and talking heads and a bit of other footage of course.

|

There are some wonderful ones,of course, but I did something unusual. I thought, we had to get the immediacy again of what had happened at Orgreave, and we also had to disprove what practically the whole of the mass media had said: that miners were vicious, they had used violence, and we knew full well that it wasn’t so; in Taking Liberties we’d turned up at a little pit village and there had been 300 cops in one tiny village policing the picket lines.

|

So what I asked the miners to do, I think there were 12 of them in the dock... We asked them to go back to Orgreave, and they hadn’t been back because it was about a year and a half later when they were on trial for riot. It was very, very serious for these guys. They could have got life. Riot carried life, and so this trial was very important. Anyway, we took them back to the site and got them to recreate what had happened to them.

|

So we literally started [as if it was] the early morning on the day that it all really erupted, [June 18 1984] and got people to run up the field and show where they had been hit and how they’d been hit. We cut it absolutely precisely with documentary footage we’d got, or with stills. We asked Leslie Boulton, who was a photographer/campaigner at Orgreave, to go back to the exact place where a policeman on horseback charged along the road – and lashed out at her head with a long truncheon. She was only saved from being seriously injured by a miner pulling her away from him, into some bushes... the image of the attack remains iconic.

|

It was because we felt nobody would believe it. Everybody had been told and believed that miners were the culprits, and we had to try and turn it around and say well actually, sometimes they are culprits, but mostly they were victims.

95 pickets were arrested at Orgreave on the 18th of June 1984, and we made a film, as I said, about the trial. Taking these guys back, it was very delicate because it had been extremely traumatic because most of them had been injured. The famous one was Russell Broomhead who was beaten over the head by a policeman's truncheon and he had a stammer and epilepsy as a result. He wasn’t in that particular film, but he was in another film. I did a follow up.

It was very traumatic for these guys, and some of them are not alive, they’ve died since. It really, really had an effect on them.

|

Anyway, one of the most important interviews of my life was one of the miners, Arthur Critchlow, sitting on the step of the police holding centre, and he recounts how he was arrested. He was beaten up and he was arrested and how his wife – it makes me cry – his wife came to see him in prison. He’s a very proud, honest, lovely guy, and he ends up being criminalised. For what? Trying to save his job, and he describes how emotional it was and how his wife came and how he wanted his kids to know what it meant to him and why he’d done it and that he wasn’t a criminal.

|

It was just an incredible interview. At one point he talks about his wife was crying so much that her nose was running. We had this terrible argument... Chris Cox was the photographer on the film, and his brother, Pete Cox edited it. We had ten weeks editing this film. Can you imagine? We had weeks to research it, we had at least ten days shoot on an hour long documentary, and we had ten weeks to cut it on film. Never before or since! It was those fantastic resources Channel Four gave you.

Pete and I had this huge row. On the whole we didn’t, but we had this huge row. He said ‘you can’t have this man describing this. It’s humiliating’; and he was crying and he was breaking down, this miner. He said ‘you’ve got to cut it before [this]’, and I said ‘no. We’re not. He gave the interview, he agreed to it, he wants his children to know what he went through; he wants the world to know what he went through’. Of course it stayed in, people agree, I'm sure, it was incredibly strong. People remember it.

But what I try to do as well as doing the emotional stories - and that’s what I've tried to do in all my films - everybody talks about the narrative and the human story, and you have to have people's firsthand experiences. But if you then just leave it at that, for me, that’s not enough in documentary making. You have to have an analysis of it - not by some voiceover. I never did voiceovers in the early days. We never did that.

Pete and I had this huge row. On the whole we didn’t, but we had this huge row. He said ‘you can’t have this man describing this. It’s humiliating’; and he was crying and he was breaking down, this miner. He said ‘you’ve got to cut it before [this]’, and I said ‘no. We’re not. He gave the interview, he agreed to it, he wants his children to know what he went through; he wants the world to know what he went through’. Of course it stayed in, people agree, I'm sure, it was incredibly strong. People remember it.

But what I try to do as well as doing the emotional stories - and that’s what I've tried to do in all my films - everybody talks about the narrative and the human story, and you have to have people's firsthand experiences. But if you then just leave it at that, for me, that’s not enough in documentary making. You have to have an analysis of it - not by some voiceover. I never did voiceovers in the early days. We never did that.

It was proper documentary making in which you’d invite the solicitor for example, Gareth Pierce, who was there representing so many of these miners to describe events - she would put the next layer of analysis of what had happened. So we’d have the personal and then we’d have the solicitor and then we had Michael Mansfield talking much more globally, if you like, about the whole situation, the political situation and the bigger context. And then we’d put it in the economic context and the historical context. We talked to really old miners in that film about the ‘20s and their struggles to save their jobs.

|

This film [The Battle for Orgreave] is a well known film and it’s been used throughout colleges and so on because it was a landmark film – and I'm very pleased because it only got one showing on C4 – I am very, very proud of it. The other thing I am proud of, which is very rare, is that seven years later, we did a follow up, and you are never normally allowed to do that in the media. We went back and the reason I was able to do it is because the miners trusted me.

|

I had not done what so many people – I'm afraid – in the media did at that time, which is lie to them and say ‘we’ll represent your point of view’ and then didn’t. We didn’t muck about, we showed it how it was, and they remembered us of course. I still get Christmas cards from those miners 20 years later, and they are friends. They have been people in my life.

|

We were able to do a sequel, a follow up, and show what had happened to people's lives, and it was quite depressing. The coalfields have been devastated. Whatever one thinks about Arthur Scargill, he was right. They closed hundreds of pits, hundreds of thousands of jobs went; we don’t have a coal industry, we have a bit of open cast mining, and those guys were right to fight. It’s a big lesson.

|

KM: It shows quite a lot of political events round the time as well, like the North Staffs Miners Wives Action Group.

YV: Yes, I went and spoke when they showed it there and at Cambridge University recently because it was the 25 years anniversary of the strike. A new film has been spun off it directed by Mike Figgis. [The Battle of Orgreave] There is a young artist who has won the Turner Prize, called Jeremy Deller, who saw my film. He didn’t know anything about Orgreave, never heard about it, saw my film at an event in Wales and rang me up and said he would like to recreate what happened at Orgreave as an art event for a big company called Art Angel.

YV: Yes, I went and spoke when they showed it there and at Cambridge University recently because it was the 25 years anniversary of the strike. A new film has been spun off it directed by Mike Figgis. [The Battle of Orgreave] There is a young artist who has won the Turner Prize, called Jeremy Deller, who saw my film. He didn’t know anything about Orgreave, never heard about it, saw my film at an event in Wales and rang me up and said he would like to recreate what happened at Orgreave as an art event for a big company called Art Angel.

KM: So you took on the whole issue of the government’s white paper proposing the implementation of a sort of American style private healthcare. You did a few films about that, but in the meantime you were continuing with this groundbreaking charity film, which won many awards.

|

YV: We did a very important film called Stand up the Real Glynn Vernon. That won a Golden Reel [ITVA]. But it was important because it was the first time we believe anyone had put a disabled person at the centre of a film. Glynn couldn’t speak clearly because he had cerebral palsy. It was very, very difficult to understand him. So we asked Dave Hill, a wonderful actor, to 'become' his voice, and we just followed Glynn around.

|

It was very simple. We had no money, it was a very small budget thing, but we just showed his world. We scripted it for Glynn/Dave after Tony Wardle spent a long time with Glynn, built up trust, he really liked the guy, and got him to open up about his life and what it was like to be stuck in a wheelchair and stuck in this body.

There was a very funny opening to the film, which revolutionised the approach to disability. Glynn says: ‘What have I not got enough of in life? I ain’t got enough money, and I don’t get enough sex.’ That’s how it started. So you’re expecting this guy to say: I can’t have access to my bathroom, or whatever - but no, he’s just like all the rest of us!

Anyway, it did open things up, because Glynn actually became the President of SCOPE, and went on to be very instrumental in changing policy and opening up the issues about disability. Unfortunately he died a few years ago.

I made a great little number – I'm proud of this one – called Councils for the Defence. It was when all the local councils were being attacked [by the Tory government], they capped them. There was a big sit in at Lambeth, and the only film crew that was allowed in Lambeth Town Hall, where all these workers were occupying it against loss of jobs and cuts in funding, was us. There was a great leader amongst them called Jim O'Brien - fine man. So we made this little film, a sort of campaigning film about that.

Somewhere along the line I also worked for Bandung File. That was quite gratifying, because Tariq Ali who was running the company I'd always known of as a sort of ‘revisionist’, because I was in one party and he was in another party of the left and there were all sorts of conflicts. I'd never met him, and he rang me. I think it was one time in my life I was headhunted. He said ‘I've seen the Battle for Orgreave, it’s the best documentary ever made’, or something, so immediately flattery won!

I went to work for them and it was a great atmosphere. There was one white male working there, all the rest were black employees or white women - it was just a really different atmosphere. What was also wonderful about that company, they were not afraid to take on or challenge stereotypes about black people. They produced very, very good programmes. The only slight problem was I was pregnant by that time and I just kept forgetting everything - maternal dementia! But I met Darcus Howe [the other company director's] daughter, Tamara who was very young and working in reception or something at the time, but she’s important later on. You always have to remember to be nice to people in this business because you never know who is going to get to a position of power later on, and she did, when it came to the Lawrence film.

So again [at Bandung] I got my team of actors, I got Jimmy Marcus back, for the programme Rat Race. I researched the film by sitting in on these racism awareness training sessions, and you’d get these facilitators saying to people ‘give me names with black in them’. So people would say ‘Blackpool’, [for example] and on this blackboard there were all these names of places and things which had black in it. They were all designated racist. So Blackpool suddenly becomes racist! You know, it was just completely over the top and ridiculous. It was quite horrifying.

There was a very funny opening to the film, which revolutionised the approach to disability. Glynn says: ‘What have I not got enough of in life? I ain’t got enough money, and I don’t get enough sex.’ That’s how it started. So you’re expecting this guy to say: I can’t have access to my bathroom, or whatever - but no, he’s just like all the rest of us!

Anyway, it did open things up, because Glynn actually became the President of SCOPE, and went on to be very instrumental in changing policy and opening up the issues about disability. Unfortunately he died a few years ago.

I made a great little number – I'm proud of this one – called Councils for the Defence. It was when all the local councils were being attacked [by the Tory government], they capped them. There was a big sit in at Lambeth, and the only film crew that was allowed in Lambeth Town Hall, where all these workers were occupying it against loss of jobs and cuts in funding, was us. There was a great leader amongst them called Jim O'Brien - fine man. So we made this little film, a sort of campaigning film about that.

Somewhere along the line I also worked for Bandung File. That was quite gratifying, because Tariq Ali who was running the company I'd always known of as a sort of ‘revisionist’, because I was in one party and he was in another party of the left and there were all sorts of conflicts. I'd never met him, and he rang me. I think it was one time in my life I was headhunted. He said ‘I've seen the Battle for Orgreave, it’s the best documentary ever made’, or something, so immediately flattery won!

I went to work for them and it was a great atmosphere. There was one white male working there, all the rest were black employees or white women - it was just a really different atmosphere. What was also wonderful about that company, they were not afraid to take on or challenge stereotypes about black people. They produced very, very good programmes. The only slight problem was I was pregnant by that time and I just kept forgetting everything - maternal dementia! But I met Darcus Howe [the other company director's] daughter, Tamara who was very young and working in reception or something at the time, but she’s important later on. You always have to remember to be nice to people in this business because you never know who is going to get to a position of power later on, and she did, when it came to the Lawrence film.

So again [at Bandung] I got my team of actors, I got Jimmy Marcus back, for the programme Rat Race. I researched the film by sitting in on these racism awareness training sessions, and you’d get these facilitators saying to people ‘give me names with black in them’. So people would say ‘Blackpool’, [for example] and on this blackboard there were all these names of places and things which had black in it. They were all designated racist. So Blackpool suddenly becomes racist! You know, it was just completely over the top and ridiculous. It was quite horrifying.

So I'm afraid we slightly took the ‘mick’ out of this in this drama vignette we did, and that caused a bit of a stir, I think, as well at the time. I did a couple of items for them. I did one on the BCCI, which was the bank that was reported for corruption.

|

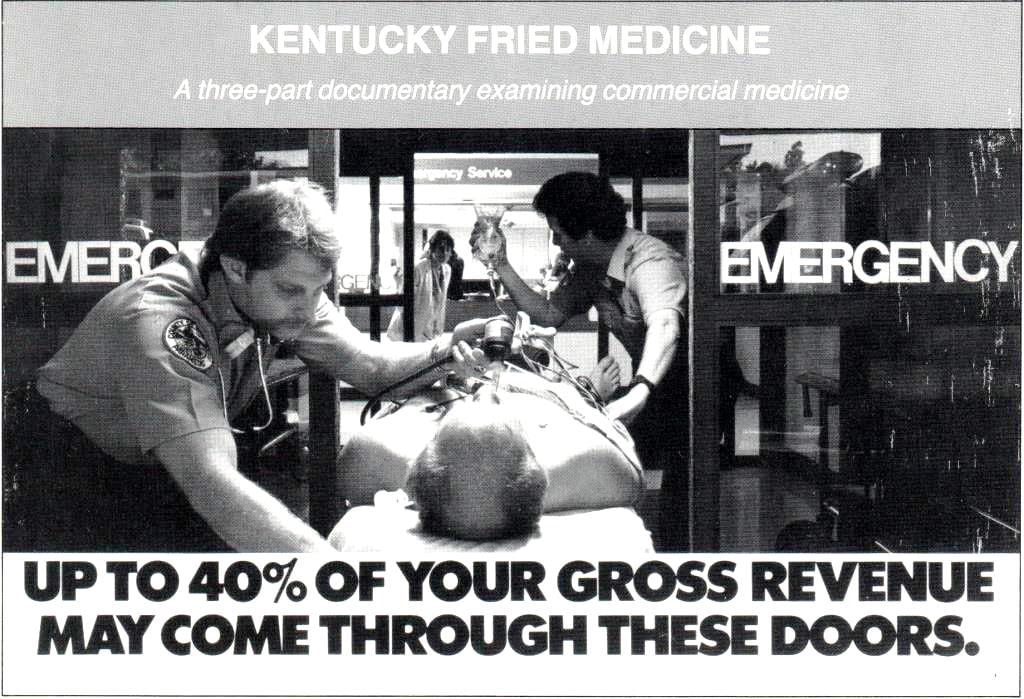

Then we did the health programmes. Kentucky Fried Medicine, that was a very important three part series. I must have been pregnant for a very long time because I was pregnant then as well - but I was only pregnant once with my son Freddy! But again, because we had no Internet or anything, we had to find people in America who were going to talk about the private healthcare system, and it wasn’t easy because there were very, very few people who were willing to criticise and risk their jobs.

|

We found some fantastic people though, I remember a wonderful doctor in Harlem called Mark Nelson - I'll never forget him, who let us film in Harlem public hospital. It was third world. There you are in the richest country in the world and you are in the third world. They had no equipment, and it was devastating. We did some incredible interviews with people: relatives of a young man who had been left out under a tree because he didn’t have insurance, he was left to die; a family man who had leprosy, which is absolutely treatable, in America, and he’d lost all the digits of his hands because he didn’t have insurance cover.

It sounds like scaremongering, but it wasn’t. These weren’t isolated cases. This was going on, and still is going on, because Clinton didn’t bring in a health service for America. We were trying to say if you privatise the health service you will get a two or three-tier system, and by stealth, it’s happened. I think one of the things - I was thinking about it today - about Vanson Wardle and Vanson Productions has been that we have been very prophetic. We’ve always been a bit ahead of the game. Were we that smart? I don’t know. We were just on the ball. Were we just politically more aware than other people?

It got very, very frustrating at times because we’d go to commissioning editors and we’d say ‘look, there’s this issue that’s boiling and burning up but it’s not right at the front of the agenda, can we make a film about it?’ ‘No, not interested’. Four years later of course, the world explodes and they wanted it, but by that time they used somebody else. An exception to that was Alan Fountain at Channel Four. Working with him… I hadn’t realised my luck until later on, because he was one of the first people I worked with on The Battle for Orgreave. He was just fantastic, and he really was a commissioning editor who fought our corner. He would go in and battle.

Every single film I have made, every single documentary I have made for broadcast has been censored, or attempted to be censored. That is not exaggerating. For every one we would have challenges, not because they weren’t well thought out, not because it was just fly on the wall, let’s throw a camera at it. They were thought out. They were researched. We had backup.

Channel Four would do incredible things. They would ring up when you’re in the cutting room. They’d seen a rough cut, it wouldn’t be Alan Fountain, but it would be higher up in the echelons, and they would ring up when you were in the cutting room doing the final cut and say we want verification… for example, we made one on low pay, and we went right round the country exploring the injustices of low pay. They rang up the day I'm finishing the film saying we need to see all the wage slips of these people to prove that they are low paid. I mean, this is people who were picking carrots in the fields. I don’t suppose they had wage slips. It was probably cash in hand. They didn’t ask to see the wage slips of the experts we were talking to, but that was the sort of attitude we encountered.

We have always talked to real people in our films. We’ve talked to working class people, we’ve talked to miners, we’ve talked to black people, we’ve talked to people that didn’t normally get on screen, and somehow there was an ethos in the broadcasters at the time, well, are they to be trusted? We need to verify everything. We always did verify everything because that’s the job. You don’t make statements and get caught out. You make sure that what is being said is true and you do it very carefully.

When we did the follow up to Orgreave, I remember being called in by Liz Forgan. Tony and I were marched into her office, which is a very rare occurrence, as I say, that the actual producers would talk to the actual head of programming. We thought what have we done this time? We knew it would be something wrong! She just said 'there’s not enough blue on the screen'. We asked what did that mean? She wanted more of the senior police officers we had interviewed about Orgreave, [in retrospect], wanted more of the interview in. We had a blazing row. Liz Forgan, if you are watching this…

Anyway, we didn’t do it - which is no doubt why I've got a hell of a reputation in the business, because we fought. I think in the end we put a caption up over a blank screen saying Channel Four tried to get clarification on so and so. I can’t remember, but we didn’t put more blue on the screen. Unfortunately there are an awful lot of commissioning editors out there who are not as brave and audacious as Alan Fountain.

It sounds like scaremongering, but it wasn’t. These weren’t isolated cases. This was going on, and still is going on, because Clinton didn’t bring in a health service for America. We were trying to say if you privatise the health service you will get a two or three-tier system, and by stealth, it’s happened. I think one of the things - I was thinking about it today - about Vanson Wardle and Vanson Productions has been that we have been very prophetic. We’ve always been a bit ahead of the game. Were we that smart? I don’t know. We were just on the ball. Were we just politically more aware than other people?

It got very, very frustrating at times because we’d go to commissioning editors and we’d say ‘look, there’s this issue that’s boiling and burning up but it’s not right at the front of the agenda, can we make a film about it?’ ‘No, not interested’. Four years later of course, the world explodes and they wanted it, but by that time they used somebody else. An exception to that was Alan Fountain at Channel Four. Working with him… I hadn’t realised my luck until later on, because he was one of the first people I worked with on The Battle for Orgreave. He was just fantastic, and he really was a commissioning editor who fought our corner. He would go in and battle.

Every single film I have made, every single documentary I have made for broadcast has been censored, or attempted to be censored. That is not exaggerating. For every one we would have challenges, not because they weren’t well thought out, not because it was just fly on the wall, let’s throw a camera at it. They were thought out. They were researched. We had backup.

Channel Four would do incredible things. They would ring up when you’re in the cutting room. They’d seen a rough cut, it wouldn’t be Alan Fountain, but it would be higher up in the echelons, and they would ring up when you were in the cutting room doing the final cut and say we want verification… for example, we made one on low pay, and we went right round the country exploring the injustices of low pay. They rang up the day I'm finishing the film saying we need to see all the wage slips of these people to prove that they are low paid. I mean, this is people who were picking carrots in the fields. I don’t suppose they had wage slips. It was probably cash in hand. They didn’t ask to see the wage slips of the experts we were talking to, but that was the sort of attitude we encountered.

We have always talked to real people in our films. We’ve talked to working class people, we’ve talked to miners, we’ve talked to black people, we’ve talked to people that didn’t normally get on screen, and somehow there was an ethos in the broadcasters at the time, well, are they to be trusted? We need to verify everything. We always did verify everything because that’s the job. You don’t make statements and get caught out. You make sure that what is being said is true and you do it very carefully.

When we did the follow up to Orgreave, I remember being called in by Liz Forgan. Tony and I were marched into her office, which is a very rare occurrence, as I say, that the actual producers would talk to the actual head of programming. We thought what have we done this time? We knew it would be something wrong! She just said 'there’s not enough blue on the screen'. We asked what did that mean? She wanted more of the senior police officers we had interviewed about Orgreave, [in retrospect], wanted more of the interview in. We had a blazing row. Liz Forgan, if you are watching this…

Anyway, we didn’t do it - which is no doubt why I've got a hell of a reputation in the business, because we fought. I think in the end we put a caption up over a blank screen saying Channel Four tried to get clarification on so and so. I can’t remember, but we didn’t put more blue on the screen. Unfortunately there are an awful lot of commissioning editors out there who are not as brave and audacious as Alan Fountain.

The early days at Channel Four were very exciting. There was a wonderful woman, Maureen, who was the head of budgeting at Channel Four, who put the budget up if necessary. She would not be there just to slash and slash, which is what happened consequently. She’d say no, you need more, you’re going to have more time, you’ll need more in the edit…fantastic, a proper dialogue about content, determining form, therefore what do we need to spend on the film? You see, over 20 years one got a bit jaded because these things were not happening.

YV: The budget was good. It was an early one at Channel Four, so the budget was good. I mean, every budget is always constrained and you can always do with more, but no, it was fine. I spent 20 odd years in the business, I never went over budget. You don’t have to. You have to cut your cloth and you have to know what you are doing. So as long as you budget, research and prepare properly and you know what you are going to see and do - it's all possible. The interesting thing about Kentucky Fried Medicine was we’d been setting it up for a long time. It was a two part series and they ended up being 66 minutes long. There was no constraint that it’s got to be 52 minutes long then. We did a 90 minute studio debate as well. Channel Four let you do what was necessary.

I remember, I'd just given birth, I'd had a caesarean, and everybody said you can’t go. You can’t go and film. It was all scheduled. It was just bad timing. I said I'm not not going. So me, superwoman, six week old baby, six weeks after a caesarean, take the baby, breastfeeding, to America, with a nanny, but every night the crew are all having a nice time and I am breastfeeding Freddy! Anyway, what the hell, I did it, and I'm glad I didn’t miss it. It was fantastic. They were powerful films.

We did a follow up documentary a few years later called Stitching up the NHS because by that time the whole pressure on the NHS was mounting and the whole privatisation debate was growing. That was an interesting one - an interesting form of censorship. That was John Willis. John Willis is highly respected, he’s a very intelligent and experienced man, but he hated our form of documentary making. He really genuinely did not like what we did. It was the antithesis of everything he believed in. He is a pure liberal, but liberal with a small L, and insisted on objectivity. We were objective, but we were objectively telling the truth. Anyway, he didn’t like Stitching up the NHS.

One of the things I always had to fight for and I always insisted on when making films, was publicity. It seems to me there’s no point in making the damn things if nobody is going to watch them. So I rang up the publicity people and I always made sure at C4, the BBC etc that the press got copies and so on, and chatted people up and tried to get showings beforehand and lots of lots of work went into promoting things. I have to say, I think every single one of our films was Pick of the Day in the press.

What happened to Stitching up the NHS? Willis knew he’d be in trouble if he tried to pull it. It had been scheduled to have 14 trails building up to transmission on the bank holiday Monday, and he pulled all the trails so that nobody knew it was going to be on! That was a very smart form of censorship, but it got a marvellous review. Fantastic reviews actually, so it didn’t quite work.

We did a follow up documentary a few years later called Stitching up the NHS because by that time the whole pressure on the NHS was mounting and the whole privatisation debate was growing. That was an interesting one - an interesting form of censorship. That was John Willis. John Willis is highly respected, he’s a very intelligent and experienced man, but he hated our form of documentary making. He really genuinely did not like what we did. It was the antithesis of everything he believed in. He is a pure liberal, but liberal with a small L, and insisted on objectivity. We were objective, but we were objectively telling the truth. Anyway, he didn’t like Stitching up the NHS.

One of the things I always had to fight for and I always insisted on when making films, was publicity. It seems to me there’s no point in making the damn things if nobody is going to watch them. So I rang up the publicity people and I always made sure at C4, the BBC etc that the press got copies and so on, and chatted people up and tried to get showings beforehand and lots of lots of work went into promoting things. I have to say, I think every single one of our films was Pick of the Day in the press.

What happened to Stitching up the NHS? Willis knew he’d be in trouble if he tried to pull it. It had been scheduled to have 14 trails building up to transmission on the bank holiday Monday, and he pulled all the trails so that nobody knew it was going to be on! That was a very smart form of censorship, but it got a marvellous review. Fantastic reviews actually, so it didn’t quite work.

KM: You spoke about how your work for charity continued throughout your career. Sort of late ‘80s quite a lot of those projects were about animal welfare. Is that something that’s quite close to you?

|

YV: Well, it wasn’t at the time, but around then we met an extraordinary woman called Juliet Gellately, Tony and I. She was the campaigns director for the Vegetarian Society. We were both absolute carnivores. I was terrible, I ate anything in sight. But we said okay, we’ll do this, and she didn’t seem to mind. She knew we made good films. That was the criteria, so we made this campaigning video for them.

|

|

You sit and watch this footage for three weeks or whatever we had... I haven’t touched meat since, nothing. Not a piece of bacon has passed my lips, and Tony has gone on to marry her and has got four year old twins with her! He is now very active in their own charity called Viva! Michael is a Patron - we're both veggie.

KM: Food Without Fear, There’s a Pig in my Pasta.

|

YV: Yes, they were hard hitting but fun too. The other thing I always thought was very important, I suppose it’s the artistic bit, the creative side of me, - music on a film is always very important. We always tried to commission original music, which went against the grain with comissioners/broadcasters. When it got to budgeting meetings they would ask why I wanted Alan Lawrence to compose the music, and I'd say because it will be better, it will really work. For Pig in my Pasta, we asked Antonio Forcione, who is an absolutely brilliant guitarist, to do the music for that, because it was all set in a little Italian restaurant. So he composed this wonderful music. I have always enjoyed working with musicians on things.

|

KM : And then you made a film about the Birmingham Six, focussing on their wives, or the women.

YV: That was purely by chance. That was because Michael had represented the Birmingham Six on appeal. We went to a dinner and I was sitting opposite Breda Power and Maggie McIlkenny, who are two of the daughters of the Birmingham Six. They were 24 at the time, and these young women were fantastic.

|

I've always got an enormous amount from the contributors to our films. That is what’s made it for me. I don't talk about the commissioning editors, to hell with that, it’s the people in the films who have been absolutely wonderful and I've got so much from them and learnt so much from them and respect them so much.

These two young women just bowled me over, and I thought why have we never heard their story? Their fathers have been in prison for 16 years, since they were eight. I approached them and I said would you like to speak, would your mothers speak, can we give a voice to the women, because at that point the Six were still in prison.

These two young women just bowled me over, and I thought why have we never heard their story? Their fathers have been in prison for 16 years, since they were eight. I approached them and I said would you like to speak, would your mothers speak, can we give a voice to the women, because at that point the Six were still in prison.

They agreed. I mean, obviously it helped that Michael was representing them. People in the press have picked up that I do the films of Michael’s cases. But so much has gone before. I'd done all this body of work, and I used to get a bit frustrated by that, but nevertheless of course, I was deeply interested in his work and the cases he was doing, and it did give me the opportunity to meet some of his clients. But if I hadn’t got the body of work to demonstrate I am actually a good and ethical filmmaker, I don’t think I'd have got the job.

|

I worked on Birmingham Wives with Ishia Bennison, who is a very good friend of mine. She’s an actress as well, but she wanted to be involved in this. She happened to be in East Enders, so we went up to meet the women and it did open a few doors. They loved her, and we got chatting and they were fantastic. They had fought for justice and they had been stalwart, and it had been very, very tough. Anyway, they agreed we could do the film.

So the first company we approached of course was Granada, because Granada had done these wonderful documentaries and dramas about the Birmingham Six and they campaigned very hard. We got completely rebuffed. We do the Birmingham Six, they said, what do you mean the women? They’d met these women but they’d never seen a story in that, which is very chauvinistic really.

|

So we thought well, to hell with Granada then, fine, we’ll go elsewhere. So we finally got an Everyman commision. And again, I only learnt after the event really that Jane Drabble, who was the series editor at the time, fought an incredible battle to get that film on. People were trying to say it wasn’t religious enough, because Everyman was a sort of religious slot. In fact there was a mention of faith, or lack of it, among these women. Oh, it was very moving. Tony did absolutely wonderful interviews with them. I was very proud of that, a very simple film, just talking like this, people telling it how it is. You don’t need to do more if it’s a powerful story.

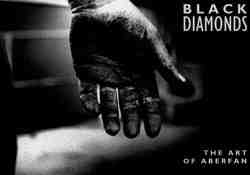

KM: Yes, good film. I think BBC Wales, you made Black Diamonds.

|

YV: Oh yes, I produced that. It was a young photographer friend of mine called Martin Dunkerton who had done some wonderful stills during the miner strike, and he wanted to make a film. He was very inexperienced. He’d never made a documentary. So I said I'd help him put it together, and we did a film on Aberfan, the terrible disaster. It was the 25th anniversary when the kids of Aberfan had died under a slurry, a coal heap. It was heartbreaking. Jimmy Dibling was the cameraman, wonderful cameraman. Again, we were lucky to have a very, very nice commissioning editor, John Geraint at BBC Wales.

|

We did another film with him on the Somali community in Butetown, Salaam Butetown, and that was very interesting as well. The war was going on and was at its height in Somalia, and this very old established community of mainly sailors who had come from Somalia and lived in the docks in Cardiff spoke about their lives. The racism, the poverty. We inter-cut it with footage of the war. It was powerful, and John was another really intelligent, caring person to work with.

What happened, we found over the years, that as soon as you meet a really good caring, intelligent, sympathetic commissioning editor, they'd go. They literally either get promoted – hopefully – or sometimes they are out the door, the revolving doors of commissioning editors, and we thought we were jinxed because we’d get to know someone and think oh, they’re going to commission us and then off they'd go! It was very difficult.

KM: So there weren’t a lot of women working at this time, so what was it like fighting your corner as a woman?

YV: It was quite tough. It’s quite isolating, but I don’t know if it was isolating because I was only one of a handful of women. I can’t remember very many others, but it was isolating being an independent producer because I was one of the first. I kind of knew Alex Graham, who started Wall to Wall at the same time. Although the independent sector grew and grew obviously, it was still difficult, and it was also particularly difficult because Tony, my partner, just hated going to those BBC open days. We had to network. You had to be there. You had to find out what the commissioning editors said they wanted, although they never really knew what they wanted! They knew what they didn’t want, and they had these open days at the BBC and they’d say for example, we want science based programmes. So everybody, the whole independent sector would rush away produce science based ideas, and by the time they were submitted, they’d changed their minds. They were inundated with so many treatments on science that they didn’t want them anymore!

What happened, we found over the years, that as soon as you meet a really good caring, intelligent, sympathetic commissioning editor, they'd go. They literally either get promoted – hopefully – or sometimes they are out the door, the revolving doors of commissioning editors, and we thought we were jinxed because we’d get to know someone and think oh, they’re going to commission us and then off they'd go! It was very difficult.

KM: So there weren’t a lot of women working at this time, so what was it like fighting your corner as a woman?

YV: It was quite tough. It’s quite isolating, but I don’t know if it was isolating because I was only one of a handful of women. I can’t remember very many others, but it was isolating being an independent producer because I was one of the first. I kind of knew Alex Graham, who started Wall to Wall at the same time. Although the independent sector grew and grew obviously, it was still difficult, and it was also particularly difficult because Tony, my partner, just hated going to those BBC open days. We had to network. You had to be there. You had to find out what the commissioning editors said they wanted, although they never really knew what they wanted! They knew what they didn’t want, and they had these open days at the BBC and they’d say for example, we want science based programmes. So everybody, the whole independent sector would rush away produce science based ideas, and by the time they were submitted, they’d changed their minds. They were inundated with so many treatments on science that they didn’t want them anymore!

I remember going to these open days and thinking who do I know here? They all seem to know me. In the end, people used to say who is Wardle, where is Tony Wardle, and I'd ask him to come with me, and he’d say no, not doing that. So I threatened to take a cardboard cut out of him to these events to prove he existed! It was tough. I was very glad to have a partner actually, to have that support, even though he hated doing the business side, the promotional side.

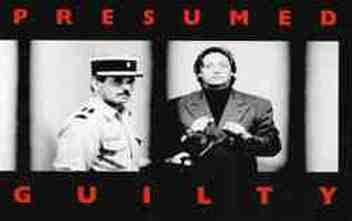

KM: We are at the beginning of the ‘90s now, and one of the projects you were involved in was Presumed Guilty, which again you collaborated with Mike Mansfield on this.

|

YV: This was Michael’s chance to rewrite the British legal system. It was very challenging, and we made it for Paul Hayman at the BBC, Inside Story, which was a very good slot, and it was an hour long. Basically what Michael tried to do, the thesis was, to put together an alternative justice system which retained the jury because juries are absolutely essential and he is a great believer in that.

|

We went to America and looked at judges in America because they have a very different approach to ours; we looked at the Juge d'Instruction, who is the person in charge of the criminal investigation in France. So we met this wonderful woman juge there, Catherine Samet, a young woman who explained much of the system.

|

It was very interesting, but again, nothing is straightforward in life. I was told categorically who I had to use as crew. I had never in my life been told who to work with. Fortunately I was able to work with Chris Morfett who’s a great guy and a very good cameraman. They accepted him, but it was like vetting of staff. They said you can’t do the film unless you have this particular editor, whose name absolutely escapes me.

|

It was awful. After that I said I will never ever do this again. You either want the film on my terms, or we don’t do it at all, because we didn’t have a rapport, he was doing the film that Paul Hayman or whoever wanted, and not the one we were trying to make.

It was another good lesson. How desperate are you as a producer to make a film? Fairly desperate because you want to make it, you think it’s important, and you also have a living to make. But you are not so desperate that you allow them to dictate those terms. We were not in trade unions for nothing, we did not make films about struggle and injustice for nothing, and it was an injustice.

Nevertheless, the film was fantastic, Michael on a butcher's bike with Chris filming from a big carrier on the front! We had great fun and it worked and it was very well received, despite all that. They can’t put you down, they can’t keep you down.

KM: I suppose it was made at a time when miscarriage of justice would have been…

YV: Yes, I suppose they were big issues. The Birmingham Six had got out by that time, which was fantastic. I'd like to think the Birmingham Wives maybe helped. We have to reflect and say, why are we making these films? We are communicators, but why are we doing it? We want to change the world, don’t we? Do we want to just reflect what’s out there, or do we want to show that maybe it’s possible to change things? I'm not so naïve to think we really do change the world, but films do have impact.

One of the reviews I was reading about Stephen Lawrence was that there are some films that really change the psyche, like Cathy Come Home, like Hillsborough maybe and The Murder of Stephen Lawrence I think was one of them. It’s important that we think about the content of what we are making, because what’s it for otherwise? I have always only made films I really, really wanted to make and am really interested in, and if people didn’t want them, well, tough, they didn’t get made.

KM: Following that, I think you mentioned earlier you worked on the issue of some of Britain's lowest paid workers, vegetable packers, grave diggers, and you made a programme for Critical Eye, How Low Can You Go?, in 1992.

YV: That was desperate. That was really difficult, because it was a good idea - low pay, nobody has ever done it. We had economists talking about this low pay economy, which is what has happened since, we have a low pay economy. And it even happened in our own industry. You know, bring your own camera, don’t have a soundman, don’t have a director, but that’s what it’s like. Michael has noticed it when he is interviewed for the News. It’s just a girl on a bike with a camera.

It’s frightening. We always had a PA, we had researchers, we had assistants so that people could learn the trade. I trained people in my office. I had young women working for me and they earned not that much. One of them, Marianna Abbotts, went on to be Head of Drama Development at Sony Pictures, another one, Lavinia Glynn Jones, we 'sacked' because she didn’t want to do what she was doing with us, so we 'sacked' her and said go off and do what you want to do! And she’s ended up being in the art department of many big films like Braveheart, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

Nevertheless, the film was fantastic, Michael on a butcher's bike with Chris filming from a big carrier on the front! We had great fun and it worked and it was very well received, despite all that. They can’t put you down, they can’t keep you down.

KM: I suppose it was made at a time when miscarriage of justice would have been…

YV: Yes, I suppose they were big issues. The Birmingham Six had got out by that time, which was fantastic. I'd like to think the Birmingham Wives maybe helped. We have to reflect and say, why are we making these films? We are communicators, but why are we doing it? We want to change the world, don’t we? Do we want to just reflect what’s out there, or do we want to show that maybe it’s possible to change things? I'm not so naïve to think we really do change the world, but films do have impact.

One of the reviews I was reading about Stephen Lawrence was that there are some films that really change the psyche, like Cathy Come Home, like Hillsborough maybe and The Murder of Stephen Lawrence I think was one of them. It’s important that we think about the content of what we are making, because what’s it for otherwise? I have always only made films I really, really wanted to make and am really interested in, and if people didn’t want them, well, tough, they didn’t get made.

KM: Following that, I think you mentioned earlier you worked on the issue of some of Britain's lowest paid workers, vegetable packers, grave diggers, and you made a programme for Critical Eye, How Low Can You Go?, in 1992.

YV: That was desperate. That was really difficult, because it was a good idea - low pay, nobody has ever done it. We had economists talking about this low pay economy, which is what has happened since, we have a low pay economy. And it even happened in our own industry. You know, bring your own camera, don’t have a soundman, don’t have a director, but that’s what it’s like. Michael has noticed it when he is interviewed for the News. It’s just a girl on a bike with a camera.

It’s frightening. We always had a PA, we had researchers, we had assistants so that people could learn the trade. I trained people in my office. I had young women working for me and they earned not that much. One of them, Marianna Abbotts, went on to be Head of Drama Development at Sony Pictures, another one, Lavinia Glynn Jones, we 'sacked' because she didn’t want to do what she was doing with us, so we 'sacked' her and said go off and do what you want to do! And she’s ended up being in the art department of many big films like Braveheart, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

You train people up. If you don’t give people that support, where does the industry go? We still say we’ve got one of the best television and film industries in the world, but I don’t know. I havn't been doing it for a bit so I don’t know what it’s like out there now, but I imagine it’s tough.

|

But we were talking about Low Pay. It was a good idea - but of course nobody wanted to be on camera! I thought oh my God, I'm making a radio programme for the first time in my life because they may only have had a low paid job, but they were terrified of losing it. So I thought halfway through the process, this isn’t going to work. What are we going to do?

|

So Tony and I were a bit desperate, I have to say - suddenly had a bit of a brainwave. We got this great comedian called Mike Elliott, who is a Geordie comedian. It was the first time ever [apart from when Michael had done his film obviously], that we’d had a presenter for a documentary, and Mike was funny. It wasn’t a funny subject, but he was funny and it just lightened the whole thing. We put him in a van and made a story of him travelling literally from John O'Groats to Lands End and interviewing people, and if they wouldn’t come on camera, if they were in the background, he could speak and we’d have their voice and he would interpret it. He did little poems and anecdotes and jokes. It was great. We got round it. There is always a way round the problem, but it was a bit scary at the time, I seem to remember.

KM: And then a film you made that year, you mentioned earlier Salaam Butetown, about the Somali community and the problems they were facing in Cardiff with employment and racial harassment. You then went on to work in the field of law with Michael Mansfield presenting Law Matters.

YV: That was good. That was the great Granada scam. Come and do ten or something inserts for This Morning, which is the Judy and Richard vehicle, and it will be like a pilot for a major series with Michael presenting really important half hour documentaries on legal issues. Excuse me, what happened to the series? We did the inserts.

Actually, it was very good discipline because the budget was absolutely nun pence, and of course Michael was in court and had very limited time. We had to film two a day of these shorts. Chris Morfett on camera a lot of the time running - stand Michael in front of that wall, put him in front of Battersea Peace Pergola talking about illegal nuclear weapons! It was all done locally [to our office]. It was just cheapskate stuff, but we managed. He was very good on camera, thank goodness, never repeated a take. You could never do two takes because he never said the same thing twice! He did legal topics like the eight hour day, about inquests, about rights at work, Sunday trading, pregnant womens' rights, and so on and so on.

KM: And then a film you made that year, you mentioned earlier Salaam Butetown, about the Somali community and the problems they were facing in Cardiff with employment and racial harassment. You then went on to work in the field of law with Michael Mansfield presenting Law Matters.

YV: That was good. That was the great Granada scam. Come and do ten or something inserts for This Morning, which is the Judy and Richard vehicle, and it will be like a pilot for a major series with Michael presenting really important half hour documentaries on legal issues. Excuse me, what happened to the series? We did the inserts.

Actually, it was very good discipline because the budget was absolutely nun pence, and of course Michael was in court and had very limited time. We had to film two a day of these shorts. Chris Morfett on camera a lot of the time running - stand Michael in front of that wall, put him in front of Battersea Peace Pergola talking about illegal nuclear weapons! It was all done locally [to our office]. It was just cheapskate stuff, but we managed. He was very good on camera, thank goodness, never repeated a take. You could never do two takes because he never said the same thing twice! He did legal topics like the eight hour day, about inquests, about rights at work, Sunday trading, pregnant womens' rights, and so on and so on.

It did go out on prime time television, and so it was good in that respect. It was a good lesson to know what you could cram into eight minutes, because up till then everybody had said you need an hour. Actually, those sorts of constraints sometimes are very good. It makes you realise you can say a lot, unlike me who goes on and on..!...but you can say a lot in a short time.

KM: And then you made Two Boys From Bangkok in 1993.

|

YV: Yes, that was for Central TV, ITV. That was very hard. That was very moving. We worked with a wonderful Catholic priest, who found us street boys, and we compared the life of a trainee Buddhist monk, a little boy and a street kid, and honestly it wasn’t much different, although one had a place to sleep, albeit on the ground, because the Buddhist monks were often ripped away from their families when very young and they had a bit of a rough time. Anyway, they were sweet kids we dealt with and it was very moving. That sold all over the world. That sold a lot, that little film.

|

KM: And then another, BBC Wales, Breaking The Mold.

|

YV: I enjoyed doing that because that was theatre, and as we started off discussing, I was an actress and I loved theatre. So Theatre Cymru in Clwyd is a municipal theatre funded by the Clwyd Council. Just as we were going to do a lovely piece with Helena Kaut - Howson, a strong Polish woman who ran the theatre, really inspirational, just as we were going to do this whole thing about the theatre, it was threatened with closure.

So it suddenly became something else, this film, the tension between them all meeting, the cutbacks and job losses and was it going to stay open? I just think maybe this film helped to keep it open. As far as I know it’s still open now, but it was really going to be closed. So that was one of my campaigning successes.

|

KM: And then Too Young to Care for BBC First Sight about the problems of young children having to look after their disabled or old parents.

YV: We’d done a film very early on, one of our non-broadcast films, we’d done way back, Tony and I, for the Department of Health and Social Services about adult carers. We always kept out of the room on these very delicate films and left Tony in the room with the contributor. A crew is quite hard-bitten a lot of the time. They’ve seen it all and been there. I turned round during one of the interviews that Tony was doing, and the whole crew was in tears. I mean, the cameraman, Peter Dugarian, couldn’t see what he was filming, we were just absolutely in floods of tears.

Tell me to be objective about these things. How can you be? These people spent 30 years of their life looking after their husband, caring, and they had no support. They didn’t have physical support, like even a shower to help, no lifts, none of that, but no emotional support. And there were desperate interviews with people saying how they wanted to kill their partner because they’d changed their personality after a stroke or something. It was very, very harrowing, but it gave us a kind of taste for the carers issue because carers were neglected. Anyway, we picked up on this story in London about young carers, and again, it was just awful, about kids having to do everything. I mean, kids at 12 having to inject their mums with insulin, for example, and of course not wanting social services involved because they were terrified of being taken into care.

So we had to be very delicate about them coming out and talking to us and not naming them, and many were on camera in fact. Interestingly, I was lying there the other morning listening to Angus Stickler doing a report on Radio Four about young carers. This is nearly 15 years later. I was so angry with the government minister coming on and saying yes, we think we need another report. I got straight on the email and I emailed Today. I said look at my film, it’s at the BFI, about young carers. Try and follow up. Why don’t you try and follow up some of those young carers and see how it affected their lives 15 years on. Anyway, they said they were going to do it, and whether they did, I was away. But these issues don’t go away.

YV: We’d done a film very early on, one of our non-broadcast films, we’d done way back, Tony and I, for the Department of Health and Social Services about adult carers. We always kept out of the room on these very delicate films and left Tony in the room with the contributor. A crew is quite hard-bitten a lot of the time. They’ve seen it all and been there. I turned round during one of the interviews that Tony was doing, and the whole crew was in tears. I mean, the cameraman, Peter Dugarian, couldn’t see what he was filming, we were just absolutely in floods of tears.

Tell me to be objective about these things. How can you be? These people spent 30 years of their life looking after their husband, caring, and they had no support. They didn’t have physical support, like even a shower to help, no lifts, none of that, but no emotional support. And there were desperate interviews with people saying how they wanted to kill their partner because they’d changed their personality after a stroke or something. It was very, very harrowing, but it gave us a kind of taste for the carers issue because carers were neglected. Anyway, we picked up on this story in London about young carers, and again, it was just awful, about kids having to do everything. I mean, kids at 12 having to inject their mums with insulin, for example, and of course not wanting social services involved because they were terrified of being taken into care.

So we had to be very delicate about them coming out and talking to us and not naming them, and many were on camera in fact. Interestingly, I was lying there the other morning listening to Angus Stickler doing a report on Radio Four about young carers. This is nearly 15 years later. I was so angry with the government minister coming on and saying yes, we think we need another report. I got straight on the email and I emailed Today. I said look at my film, it’s at the BFI, about young carers. Try and follow up. Why don’t you try and follow up some of those young carers and see how it affected their lives 15 years on. Anyway, they said they were going to do it, and whether they did, I was away. But these issues don’t go away.

So when people say what can we make a film about, there is no difficulty. You can go back over things. Unfortunately, political issues and politicians are more concerned with waging wars than dealing with some of these crucial domestic issues.

|

KM: Then there was another BBC education special, Taken For Granted.

YV: This was another one of our sort of prophetic films, because it was 1994, I think, and the whole issue of student grants and loans was just coming up. And again, it was a very simple film just interviewing young students who were working class, middle class, wherever they were from, either their parents wouldn't support them or couldn’t support them, getting into debt, dropping out, very sad.

|

|

Of course now, this boy who I had all those years ago, he’s nearly 20 now, Freddy, is going off to university this year. He’s lucky he’s got a dad who can pay for it. But it’s shocking, really bad now. I am a political animal and we actually thought Labour might not do things like this. We had the benefit of free education, and the burdens on kids today are really, really heavy.

|

I did sit in the edit for that and think I am nearly at the end of my film career because I'd made this programme in my head. When you’ve been making films for that amount of time and you engage with the people and you are really committed to the subject, nevertheless, you kind of make them in your head before you’ve actually filmed it. I remember sitting there thinking oh, do I really want to sit here for a week or two in the edit? So, it was the beginning of me thinking maybe I'll change tack, which I did a bit, after some drama.

KM: Then you made another training film for the BBC, which won a Royal Television Society’s Adult and Education Training Award, Making Advances.

|

YV: That was a big series - a five part series, on which I specifically decided to employ female crew - camera, editors, director, Susan Barrett directed some of them. it was about sexual harassment at work. I remember the commissioning editor, I don’t remember his name, he was not one that you remember, saying I think what we’ll do is we’ll just get an office that will agree to let us put up secret cameras above the photocopier or somewhere and you can edit the outcome and show real sexual harassment! I said I don’t think so.

|

I'm not sure people are going to actually harass people or tweak bras or whatever they do when the cameras are there, although they might. But nevertheless, is this what’s really important about this? No. So we had long debates about how we were going to do this. In the end, we hired a studio and filmed a lot of drama reconstructions, using wonderful actors. We recreated scenes of what had happened to the women, and inter-cut them with these – I have to say – absolutely amazing interviews with women who had been harassed.